Pytorch Autograd

This post serves as a note after reading Pytorch autograd docs and this tutorial

Pytorch offers an efficient way of computing gradient, particularlly useful for high dimensional functions.

Let’s then just dive right in some codes and then I will explain each line of them.

import torch

import numpy as np

# create a 1D tensor and enable gradient

x = torch.randn(3, requires_grad = True)

# one other way to create a tensor

x = np.arrary([1., 2., 3.])

x = torch.from_numpy(x)

# and then enable the gradient

x.requires_grad_(True)

# define a function in terms of x

y = x*x + 4

# backward propagation

y.backward(x)

# get the partial or direct gradient

x.grad

Above is a very basic use of Pytorch autograd. Let’s explain every detail:

-

Tensor is, in simple, an n-dementioanl array. In above example, we use \(2\)D array but is converted the form of tensor because Pytorch uses tensor for manipulation, not numpy array.

-

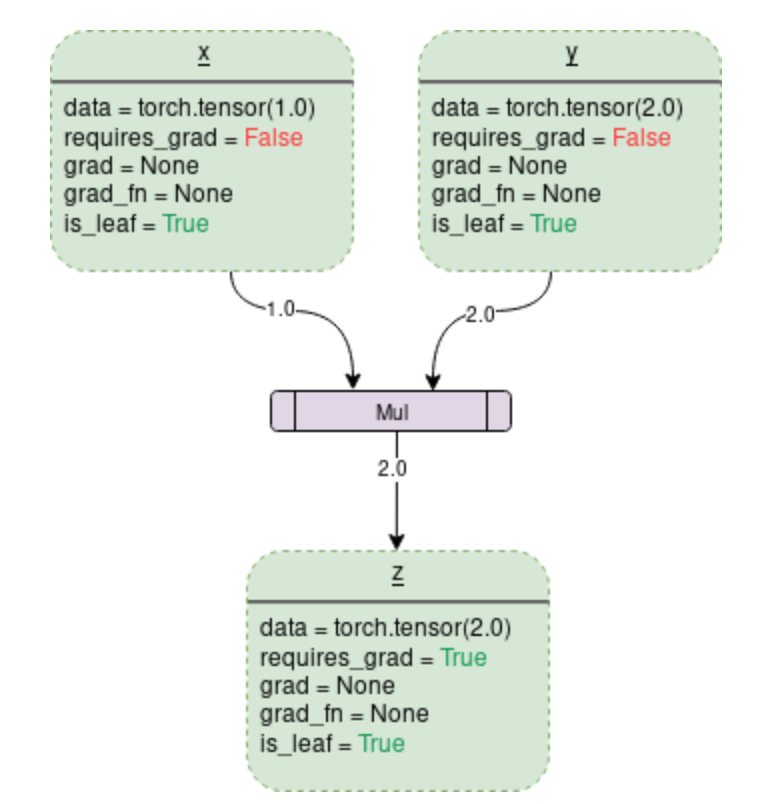

dynamic computation graph (DCG) is a backward graph that tracks every operation apploed on them to calculate the gradients. The leaves of this graph are input tensors and the roots are output tensors. Gradients are calculated by tracing the graph from the root to the leaf and multiplying every gradient in the way using the chain rule. A simple DCG:

Data: It’s the data a variable is holding. For example, x holds a \(1\)x\(1\) tensor with the value equal to 1.0.

requires_grad: If this attribute is true, then this tensor starts to track all the operation history and forms a backward graph for gradient calculation. For an arbitraty tensor \(a\), it can be done in place by a.requires_grad_(True). Note that only tensors of floating point dtype can require gradients. That’s why I initiate like this x = np.arrary([1., 2., 3.])

grad: grad holds the value of gradient. If requires_grad=False it will hold a None. Even if requires_grad=True, it will hold a None unless .backward() is called.

.backward(): This is the function that actually calculates the gradient by passing its argument through the backward graph all the way up to specific traceable leaf. Note that .backward() without argument passed is default for scalar output. Actually, it automatically passed as .backward(torch.tensor(1.0)). This means that if we the gradient we want to compute is not a scaler tensor, we should explicitly pass an external gradient of the same dimension input tensor. Take the code above as an example, we want to compute the gradient of x = tensor([1. ,2. ,3.]), we should use .backward(torch.tensor([1. ,1.])) (you can pass different tensors, e.g. torch.tensor([\(0.5 , 0.5\)]), it just shrinks the direct gradient by \(2\)–that’s why it’s called external gradient, or upstream gradient). And note that the backward graph is already made dynamically during the forward pass. Backward function only calculates the gradient using the already made graph and stores them in leaf nodes.

I want to specifically point out a confusing use of .backward() that many people have trouble understanding:

x = torch.tensor([1., 2.], requires_grad=True)

y = x * x + 2

y[0].backward()

x.grad # tensor([2., 0.])

You might be wondering, I just said that if we want a vector output, we should explicitly pass input gradient as an argument of .backward(), then why does above code work fine?

Actually, when you look at the code, I used y[0] which means I just computed the gradient of a scaler, i.e. the first dimention of input. That being said, the output is indeed a scaler but because we ignore the rest dimensions(in this example, the second dimension), we do the zero-filling.

Another tricker example is

x = torch.tensor([1., 2.], requires_grad=True)

y = 2 * x[0] * x[0] + 4 * x[1] * [1]

y.backward()

x.grad # tensor([4., 16.])

We don’t get an error in this case because although it looks like we output a vector, we essentially sequentially output two scalers and then put two scalers in a list as the final output. This manipulation happens a lot in neural nets where x[\(0\)] is the weight, and x[\(1\)] is the feature.

grad_fn: This is the backward function used to calculate the gradient

To stop Pytorch from tracking the history and forming the backward graph, you can either call .detach() or wrapp the code inside with torch.no_grad(): It will make the code run faster whenever gradient tracking is not needed by saving memory. This is particually useful when evaluating a model where we don’t need the gradients even with trainable parameters with requires_grad=True

import torch

#creating the DCG

x = torch.tensor(1.0, requires_grad=True)

y = x*2

# check if tacking is enabled

print(x.requires_grad) #True

print(y.requires_grad) #True

with torch.no_grad():

#check if tracking is enabled

y = x*2

print(y.requires_grad) #False

In earlier versions of Pytorch, the torch.autograd.Variable class was used to create tensors that support gradient calculations and operation tracking but as of Pytorch v0.4.0 Variable class has been deprecated. torch.tensorand torch.autograd. Variable are now the same class. More precisely, torch.tensor is capable of tracking history and behaves like the old Variable.