OOP Design Pattern - Strategy Pattern

This is the first of a series of posts discussing some common object-oriented programming (OOP) design patterns. I am using head first design patterns as my reference. I also recommend watching the video series from Chris to have a better understanding of this topic. Unlike previous posts, I will try to use Feynman technique. That being said, I will try to limit the word ccount to \(50\) to explain what each design pattern is, and I want to know if you can understand, if not thoroughly, the gist of each of them. I will also include elobaration at the end of this post, for the sake of tutorial and self-refresh. Today is about strategy pattern.

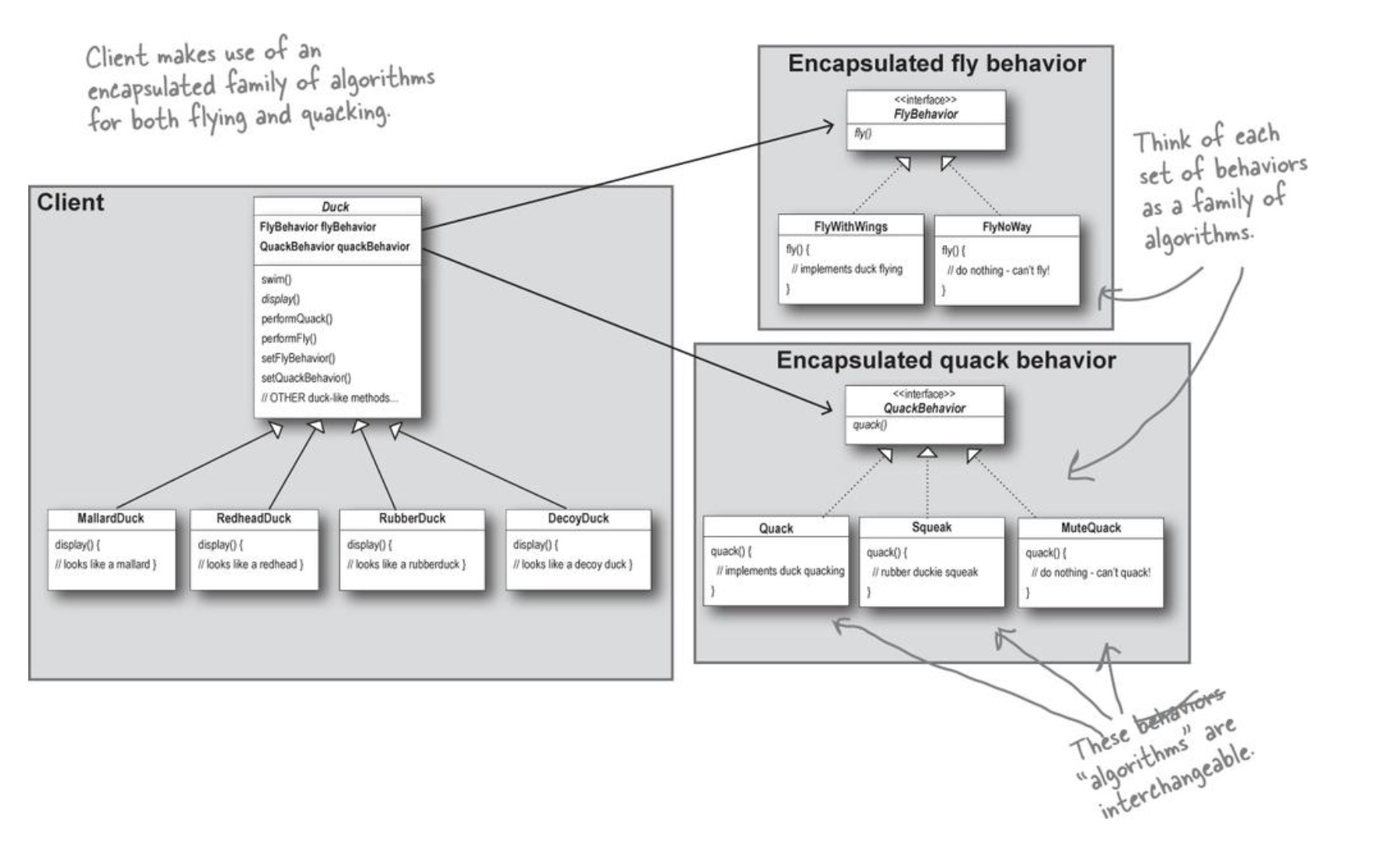

Strategy pattern encapsulates various algorithms and gives client (whoever is using the code) the choice to use them. This pattern favors composition instead of inheritance. Here an algorithm is a specific method/function of which the usage is usually varying from client to client.

Further discussion

I am now using a Duck example. Suppose you want to write a OO program that realizes two ducks, say DuckA and DuckB, which both have the ability to eat and quack. And you are like, it looks like an inheritance problem which I can create a Duck class that has these two methods, and then have two Ducks extend this class. Something like this:

public class Duck{

void quack(){

system.out.println("quack...quack...");

}

void eat(){

system.out.println("eat...");

}

}

public class DuckA extends Duck{

DuckA(){

super();

}

}

public class DuckB extends Duck{

DuckB(){

super();

}

}

Everything looks good right? Now I want to introduce the thrid type of Duck called DuckC that couldn’t quack, say, a toy duck. If we do the same thing for this duck by creating a class extending Duck, it’s meaningless to have this quack() method for it, isn’t it? Actually, it violates the fact by giving it the ability to quack. How to solve it? Easy. Let’s just override quack in DuckC and have it do nothing.

public class DuckC extends Duck{

DuckC(){

super();

}

@Override

public void quack(){

// do nothing

}

}

Perfect. Problem solved. Okay, now, I want to introduct yet another type of Duck which can quack but not eat. You just do the same thing for DuckC but override the eat class right? However, think about the situation when DuckC one day become quackable. You’ll then have to change the implementatio of DuckC. Well, you might figure an interface is a good idea. For each behavior, we create an interface and only have a concrete Duck implements the the ones it supports.

class interface Quack{

void quack(){

system.out.println("quack...quack...");

}

}

class interface Eat{

void eat(){

system.out.println("eat...");

}

}

class DuckA implements Quack, Eat{

}

class DuckB implements Quack, Eat{

}

class DuckC implements Eat{

}

This is probablly the worst implementation because for every concrete Duck we have duplicate codes, meaning that a modification on one strategy will require you to modify all codes. Now you should kind of get the idea why what we’ve done so far is not a good practice. By brining in more kinds of Duck, you have to override different methods depending on which methods they supports and which they don’t.

This will get messy when you have many subclasses and many methods (in our case, just two, quack() and eat()). This is when strategy pattern comes into play.

Remember when I briefing this pattern, I said it encapsulates vaious algorithms. Here an algorithm is a specific and conrete implementation of a duck action, like quack(). This is done by first creating two stratey interfaces, say QuackStrategy and EatStrategy. Second, for whatever the actual actions are, just simply implement the interface.

class interface QuackStrategy{

void performQuack();

}

class class NormalQuack implements QuackStrategy{

public void performQuack(){

system.out.println("quack...quack...");

}

}

class interface MuteQuack implements QuackStrategy{

void performQuack(){

// noop

}

}

Same thing for eat.

class interface EatStrategy{

void performEat();

}

class class NormalEat implements EatStrategy{

public void performEat(){

system.out.println("eat...");

}

}

class interface NoEat implements EatStrategy{

void performEat(){

// noop

}

}

Recall I also mentioned that composition is favored over inheritance. Here is how:

public class Duck{

EatStrategy eatStrategy;

QuackStrategy quackStrategy;

void quack(){

quackStrategy.performQuack();

}

void eat(){

eatStrategy.perfomEat();

}

}

public class DuckA extends Duck{

DuckA(){

eatStrategy = new NormalEat();

quackStrategy = new NormalQuakc();

}

}

public class DuckB extends Duck{

DuckA(){

eatStrategy = new NormalEat();

quackStrategy = new NormalQuakc();

}

}

public class DuckC extends Duck{

DuckA(){

eatStrategy = new NormalEat();

quackStrategy = new MuteQuakc();

}

}

public class DuckD extends Duck{

DuckA(){

eatStrategy = new NoEat();

quackStrategy = new NormalQuakc();

}

}

A Duck Has-A an eatStratey and a quackStrateg that is only determined at run time.

Finally, we have this overral UML

Why this pattern is helpful?

Some of the downsides for inheritance and overriding are mentioend above. Strategy pattern is for solving those. Imagine one day you want to modify a behavior. With pure inheritance, you’ll have to track down the subclasses and find where that method is defined. On the contrary, it’s way easier and less error-prone for strategy pattern to do so.